We all know that the economy moves in cycles; boom is followed by bust is followed by boom seemingly forever. A question we’d all like the answer to is: “Where are we now in the cycle?” Economist Hyman Minsky’s “financial instability hypothesis” helps answer this question.

Classical Economics Assumes the Market Is Fundamentally Stable

An assumption underlying classical economic theory is that the economy is fundamentally stable and seeks equilibrium. The theory holds that as excesses occur, rational market actors see the excesses and act to make money or avoid losing it, and thereby move the economy back toward equilibrium.

According to this theory, bubbles and crashes are caused by external shocks to the economy such as disease, wars, and technological discoveries. While external shocks, such as the OPEC oil embargo of the 1970s or the current pandemic, certainly have significant economic effects, they don’t adequately explain the sequence of booms and busts that we have seen. The dotcom bust of 2000 and the financial crisis of 2008 weren’t caused by external shocks; they illustrate that the economy is not fundamentally stable.

Minsky Proposed that The Market Is Fundamentally Unstable

Hyman Minsky was an economist at Washington University in St. Louis from 1965 to 1990. He proposed a theory he labeled the financial instability hypothesis, which holds that the economy creates its own bubbles and crashes. The gist of his theory is that stable economies sow the seeds of their own destruction because stability, seeming safe, encourages people to take risks. That risk-taking creates financial instability that eventually results in panic and crisis.

Unfortunately, during his lifetime, neither Minsky nor his hypothesis was taken seriously. He died in 1996, before the dotcom bubble and the Great Recession, both of which gave credence to his ideas. His theory is now accepted as a primary explanation for the boom-and-bust cycles in the economy.

The financial instability hypothesis is rooted in swings between excessive risk-taking and the panic that follows when the risk-taking overheats and the economy collapses. Increased risk in the economy can be seen in the terms on which debt is incurred. Minsky hypothesized three stages of lending he dubbed hedge, speculative, and Ponzi.

During the hedge stage, lenders and borrowers are cautious because of the losses they incurred in the prior recession. Borrowers are wary of leverage, and lenders make loans in modest amounts with stringent credit requirements. During this stage, the amount of debt in the system is reasonable.

In the following speculative stage, market participants become more confident of a recovery. Borrowers take on greater amounts of debt, and the economy begins to boom. Lenders grant credit based on ever-lower standards, assuming that asset prices will continue to rise. During this stage, borrowers can cover the interest on the loans, but become less able to repay the principal.

By the final Ponzi stage, lenders and borrowers have forgotten the lessons of the prior crisis. Everyone is sure that asset prices will continue to rise, and debt is granted with repayments based on that assumption. The economy becomes over-leveraged; debt and risk-taking have created a financial house of cards.

Finally, a “Minsky Moment”—as the New Yorker dubbed it in 2008—occurs. Market insiders take profits, everyone panics, and a crash ensues before the cycle starts over.

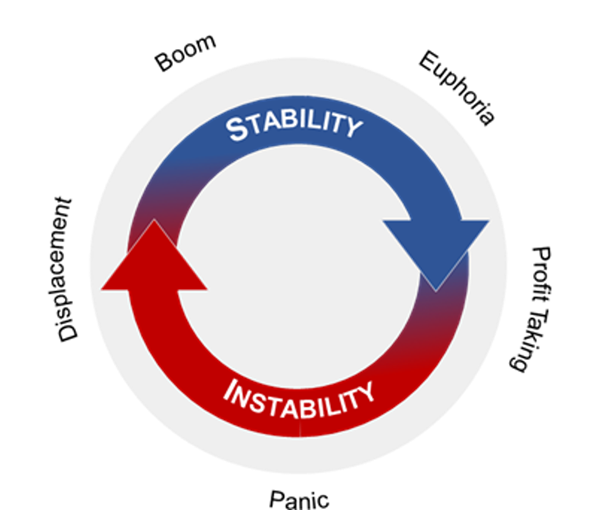

The key insight of Minsky’s model is that stability itself is destabilizing (see figure below) because during times of economic stability, healthy investments lead to speculative euphoria, increasing financial leverage, and over-extending debt, eventually resulting in a Minsky Moment, which leads to a recession or even a financial crisis.

Minsky’s Cycle of The Economy

Paradoxically, Minsky’s hypothesis teaches us that the time of greatest investment risk is when everything seems good, and investing is actually least risky when, as Baron Rothschild once put it, there is “blood in the streets.”

How Minsky Can Help Us Be Better Investors

Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis is an essential mental model for us to have in our toolkit. Each cycle has its own characteristics and length. Euphoria and panic can both last longer than we might expect. And outside shocks such as a pandemic or geopolitical events can have big effects as well. So, we can’t predict with precision when the economy will transition from one part of the cycle to the next.

But knowing roughly where we are in the cycle can inform good strategies for investors and business owners. As the economy and markets move from boom to euphoria, it’s essential to have a healthy margin of safety in the form of cash and high-quality bonds. Smart businesses will increase their cash to shore up liquidity and resist the temptation to take on more debt. Then when the profit-taking and panic occur, they can redeploy their safety margin into bargain-priced risk assets.

The most important lesson to take from Minsky’s hypothesis is not to get caught up in the fear that comes with the panicky part of the cycle, or the greed that accompanies the euphoria. While it’s not possible to accurately time the tops and bottoms of the market, knowing roughly where we are in the cycle may help you stick with your investment strategy and avoid following the herd at full speed into a bust.