Initial public offerings (IPOs) tend to be highly anticipated events for investors. (Welcome, Instacart! Hello, Arm Holdings!) An IPO refers to the process of offering shares of a private corporation to the public for the first time. Every existing public company has at one point been private and likely went through this process.

A healthy IPO reception (i.e., the price jumps that first day) is a motivating factor for other private companies that are hoping to go public. You can imagine the management teams of these private companies wondering, “Will the market absorb my new shares and carry me on their shoulders? Or will I receive a ‘Stan Kroenke returns to St. Louis’ type of reception?” Well-received IPOs encourage more IPO activity, which expands investor opportunity.

The question then posed to investors is: should you get a piece of this IPO action? Should you invest?

First, we look back on the closest followed metric for IPO performance – the first-day return.

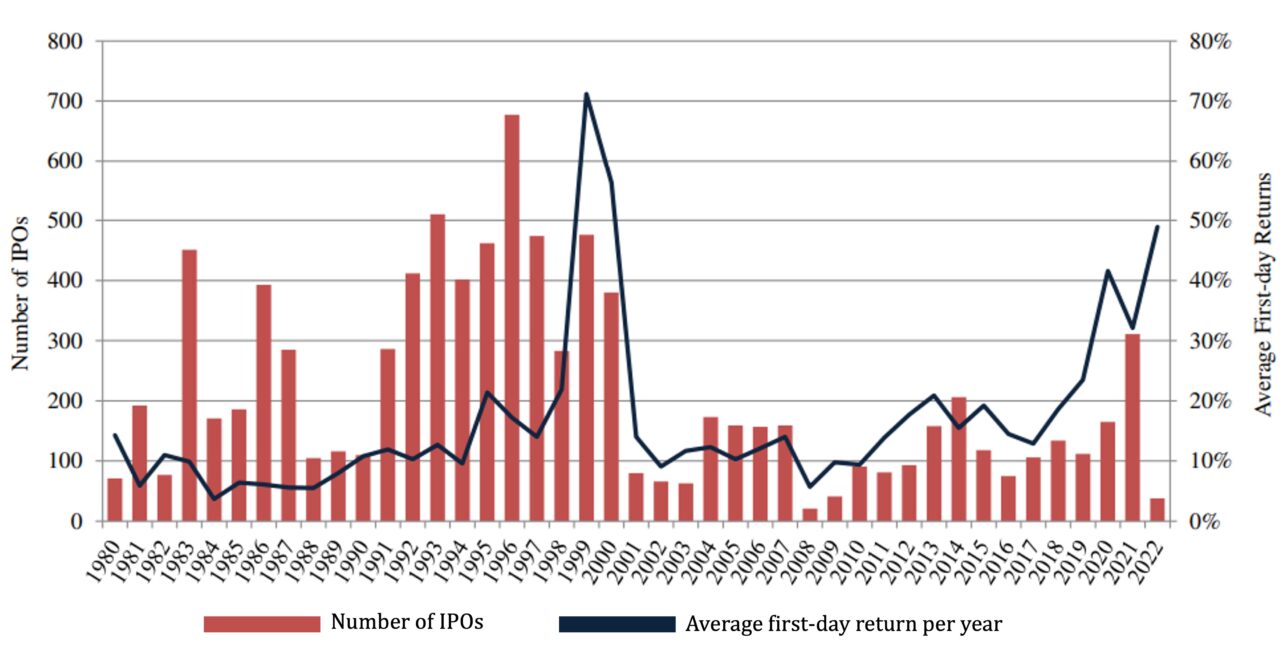

Number of IPOs and Average First-Day Return Per Year

1980–2022

The chart above shows the number of IPOs that occurred each year going back to 1980 and the yearly average first-day return. How about those 1990s?

Trying to explain to someone younger what the Dot-Com bubble was like can be hard. “You know that recent crypto bubble where we heard about NFTs and Dogecoin ad nauseum, then months later prices crater and it’s as if no trace of those things exist in conversations? Well, picture that euphoria and bust for about half the stock market and millions of affected people.” IPOs in the tech bubble hit different. The average first-day returns on IPOs reached 70% in the late 90s. (That’s an average!)

Throughout the past 40+ years, IPOs, on average, have performed well that first day. Investors have been eager to get their hands on these stocks. Seems like any investor should always buy an IPO and sell after that first day, right?

Well, it’s not so easy.

The key to receiving that first-day bump is to have possession of those shares before the market opens in order to get that ‘offer price.’ When private companies go public, they’ve engaged investment bankers (e.g., Goldman, JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley, etc.) to help prepare their required SEC filings and get into public company shape, so to speak. These bankers steward the company through the process and in return, offer to place these initial public shares primarily in the hands of sophisticated, long-term investors that promise to hold these stocks a long time institutional investors that have strong relationships with the banks and reciprocate with paid fees and services. John and Jane Smith investors tend to get excluded from this equation and must buy these stocks as the price rises or after that first close.

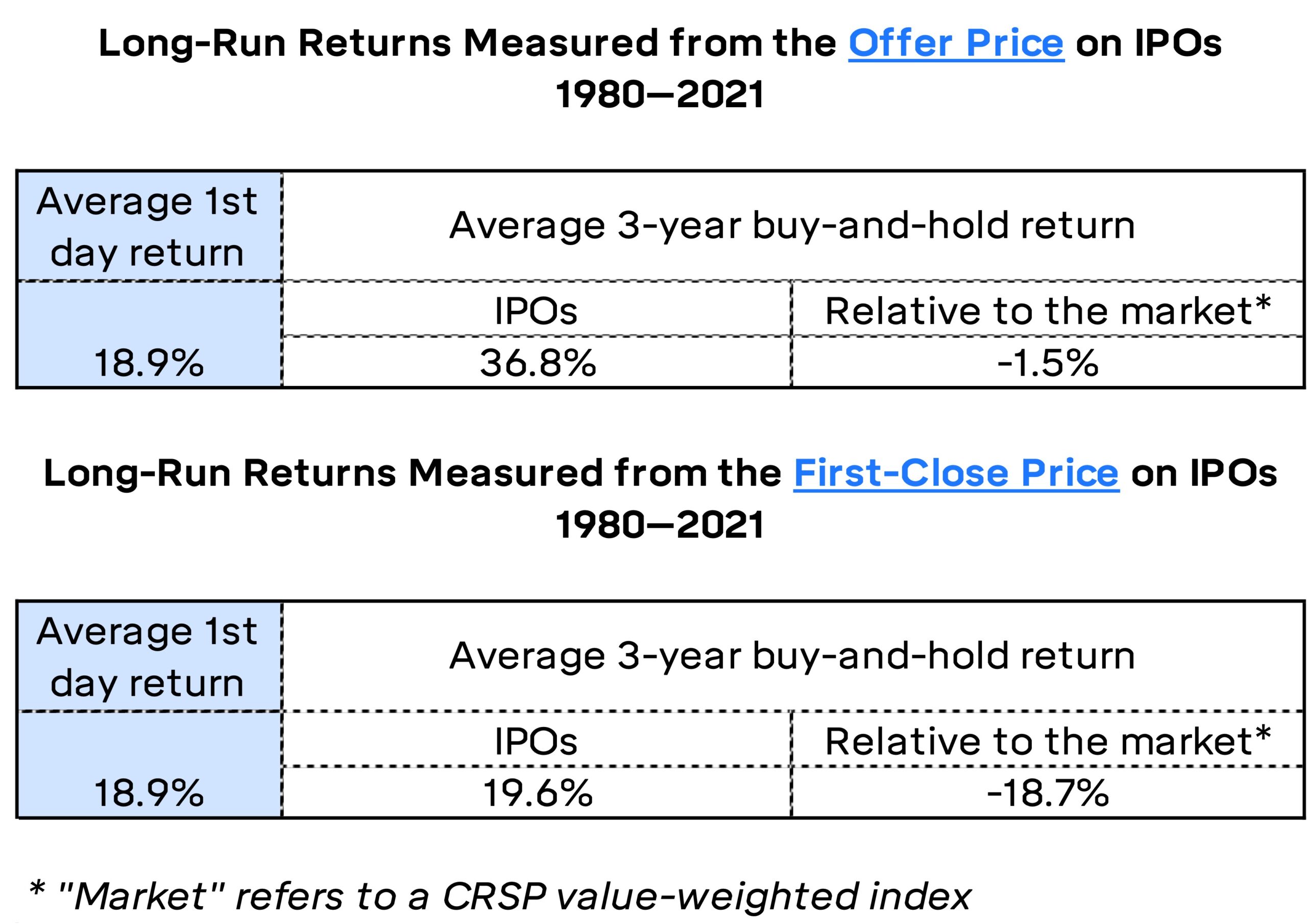

Fortunately, we are all buy-and-hold type investors, so how does the average IPO perform on a 3-year basis?

The longer-term returns have been OK, but not necessarily better than the market. This shouldn’t be discouraging, but instead a recognition that initial hype and enthusiasm aren’t criteria for successful investing. So, don’t worry about IPO FOMO – the long-term returns of a diversified portfolio are plenty deserving of hype.