Higher interest rates are a double-edged sword. They increase returns for savers and lenders but raise costs for borrowers, including the federal government.

From 2009 until early 2022, rates were super low in the U.S., but then the era of cheap money disappeared nearly overnight as the Federal Reserve increased rates from near zero to over 5% in less than a year and a half. And rates will likely remain elevated for the foreseeable future.

From a borrower’s perspective, the pre-2022 period was pretty great, and both consumers and companies took full advantage by locking in low interest rates for long periods, insulating them from the full impact of higher rates. (Note that the limited effect of higher rates on consumers and corporations is part of the reason that the rate hikes haven’t been entirely successful in taming inflation.)

The same dynamic can’t be said for the federal government. The US has been a serial debt issuer as it continually needs to borrow to fund spending needs and fill deficits. The US Treasury, too, reaped the advantages of low-interest rates and issued trillions of dollars of Treasury bills, bonds, and notes during the 2009-2021 years. Presently, the weighted average interest cost for the U.S. Treasury is 2.5% (not bad!). But unlike consumers and corporations who locked in long-term debt at low rates, the Treasury has a less-than-ideal reality – about 50% of its debt will roll off in the next two years, and they will need to replace it and add more at the higher rates (the cost of borrowing for the Treasury at various maturities sits between 3.8% and 5.5%)

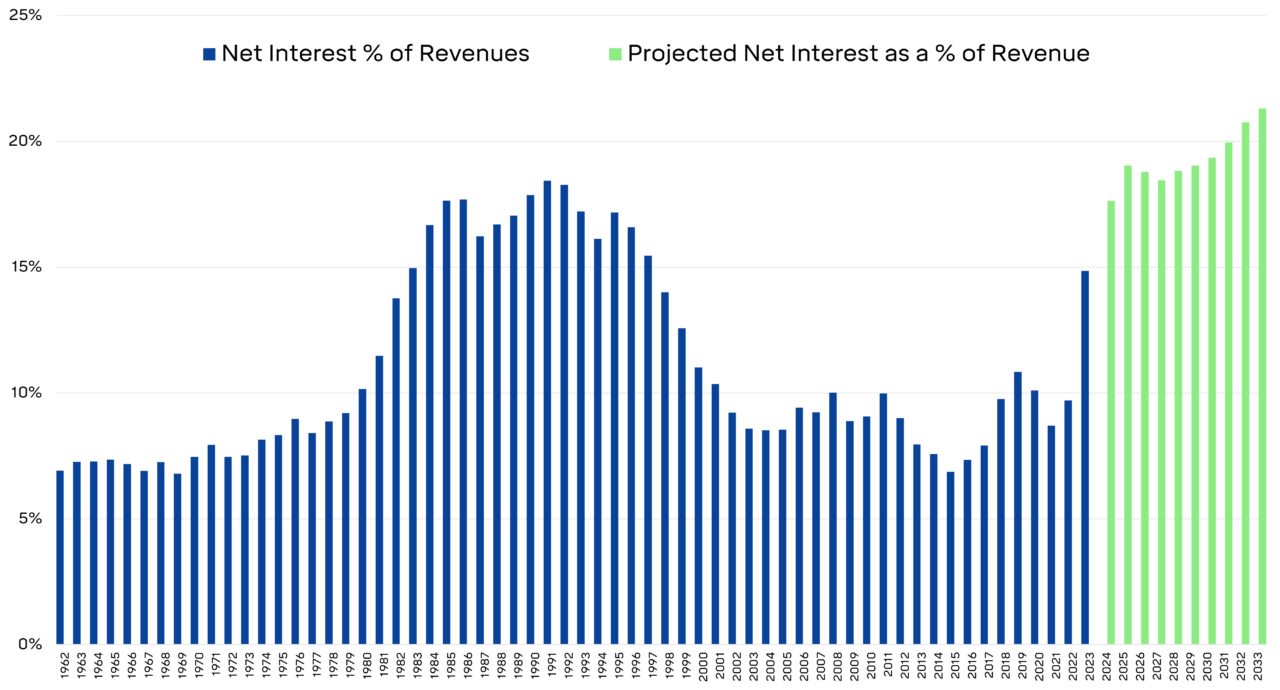

Issuing debt at these higher rates will cause the amount of interest the US Government pays to balloon. Below is a chart showing the actual and projected interest expense as a percentage of revenues for the U.S. government. You can see that interest payments will jump to a level not seen since the 1970s — what was less than 10 cents of every dollar going to service interest will double in the coming decade.

Past and Projected Federal Government Interest Payments as a Percentage of Federal Tax Revenue

The Treasury’s increasing interest expense is bad news for our government’s finances, but is that a bad omen for financial markets? Historically, no, as stocks and bonds have had a history of looking past fiscal woes, as stock and bond markets are influenced by a more comprehensive list of factors, including economic health and stability, corporate earnings and outlook, interest rates, and monetary policy, valuations, innovation, and geopolitical events. Plus, a diversified investor shouldn’t be overly exposed to any blast zone from fiscal policy. And on a more patriotic note, you can always purchase Treasuries and earn a tasty 5% rate.