Years ago, my colleagues and I were asked to evaluate the investment portfolio of a prospective client family. The portfolio was invested in a mix of traditional assets like muni bonds and public stocks, as well as healthy allocations to venture capital, private equity, and private real estate. The portfolio was well diversified, and their underlying investments had done well, especially their private equity and real estate funds. Despite this, the portfolio’s long-term performance was lackluster. Why? The reason was simple: they kept a large amount of cash to fund private investment capital calls, and the cash had dragged down their strong private investment performance to less than what they’d have earned in a stock index fund.

That family isn’t alone in finding cash management of private investment capital calls challenging; it’s a common topic of conversation (and consternation) at family office conferences. Balancing the need for liquidity with the desire to avoid cash drag is challenging for everyone.

Private Investment Fund Primer

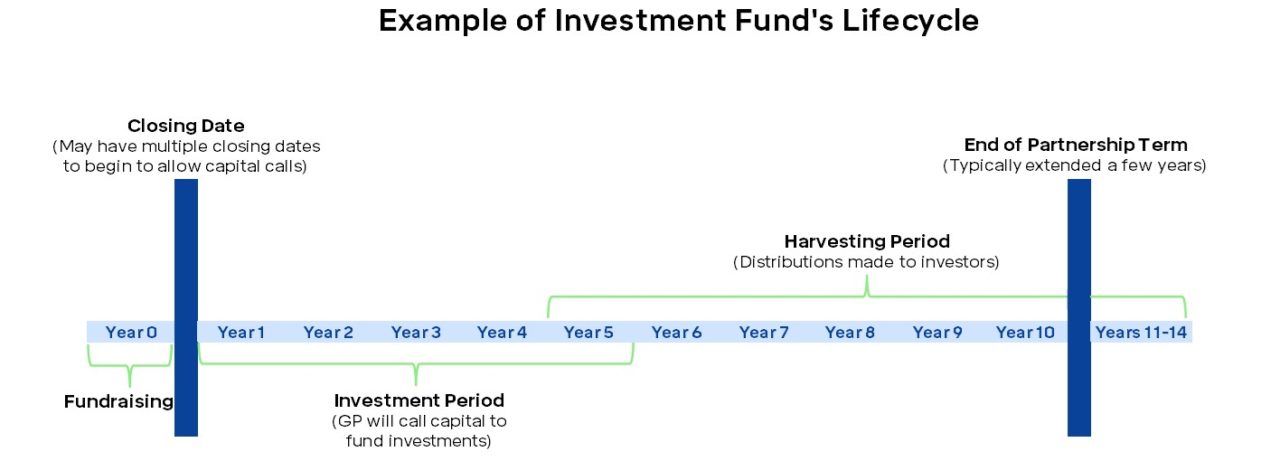

Private investment funds such as venture capital, private equity, and private real estate are structured as investment partnerships (or LLCs). The partnerships typically have a ten-year term plus the partners’ ability to extend the period by 2 – 5 years.

The general partner (“GP”) fundraises commitments from investors (the limited partners or “LPs”), which are called over a 3–6 year period as the partnership invests in businesses or real estate. The partnership distributes proceeds from the sale of its investments to the LPs during the second half of the partnership’s term. The below chart illustrates the typical private investment fund’s lifecycle.

For example, assume an ultra-high-net-worth investor named Jane. Her investment advisor suggests that she invest in a private equity fund called “Sand Valley Ventures Fund III.” The Sand Valley GPs target raising $200 million from investors over the next year and have set a closing date of September 30th, at which point their fundraising will “close,” and they won’t take on any additional investors. Jane decides to commit $1 million. She won’t transfer any money to the fund now — her $1 million will be due in chunks over the next six years when the GP calls the commitments from its investors. The exact timing of the capital calls is unknown, and Jane will likely receive little advance notice when a call is due (sometimes a week or less).

Sand Valley Ventures Fund III will use the called capital to invest in private companies. After the investment period, the GP will sell the companies owned by the partnership — hopefully at a profit — and will return the proceeds to the LPs (less the GP’s compensation).

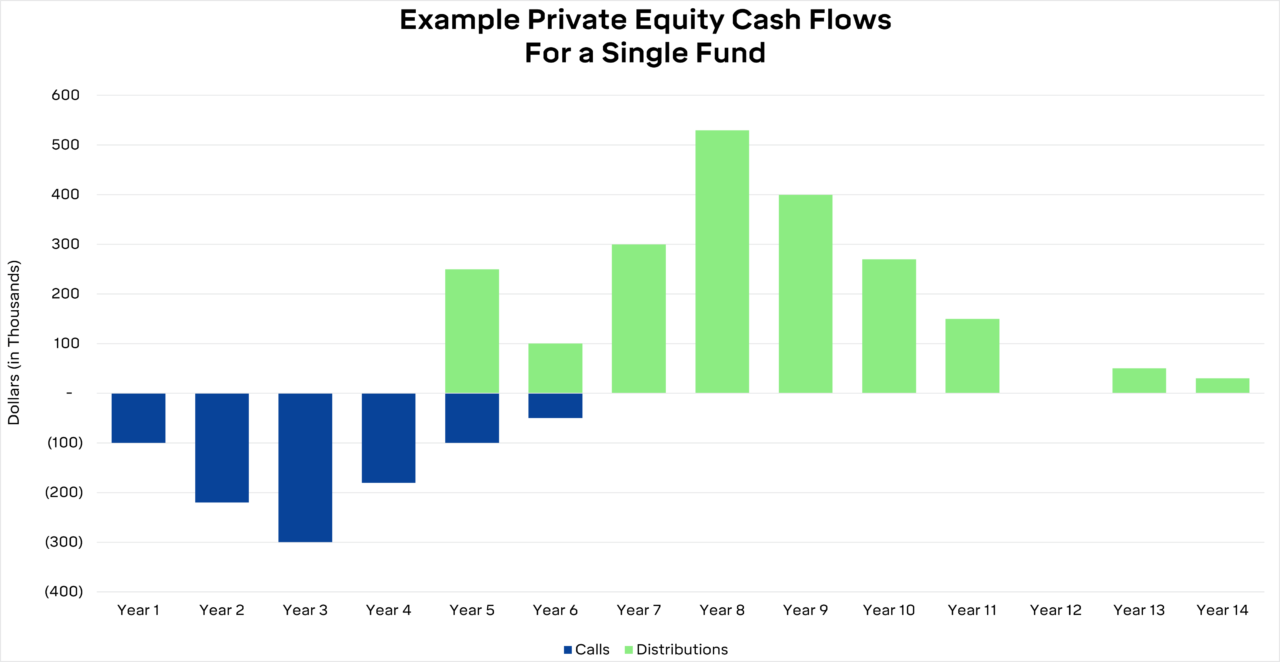

From Jane’s perspective, the cash flows into and out of Sand Valley Fund III might look like this:

Examining the above graphic, you can see the cash management challenge: Jane will need $1 million of cash to meet the GP’s capital calls over the coming five or so years, and then she’ll need to invest the distributions she receives (which in the chart above total $2 million) both timely and strategically.

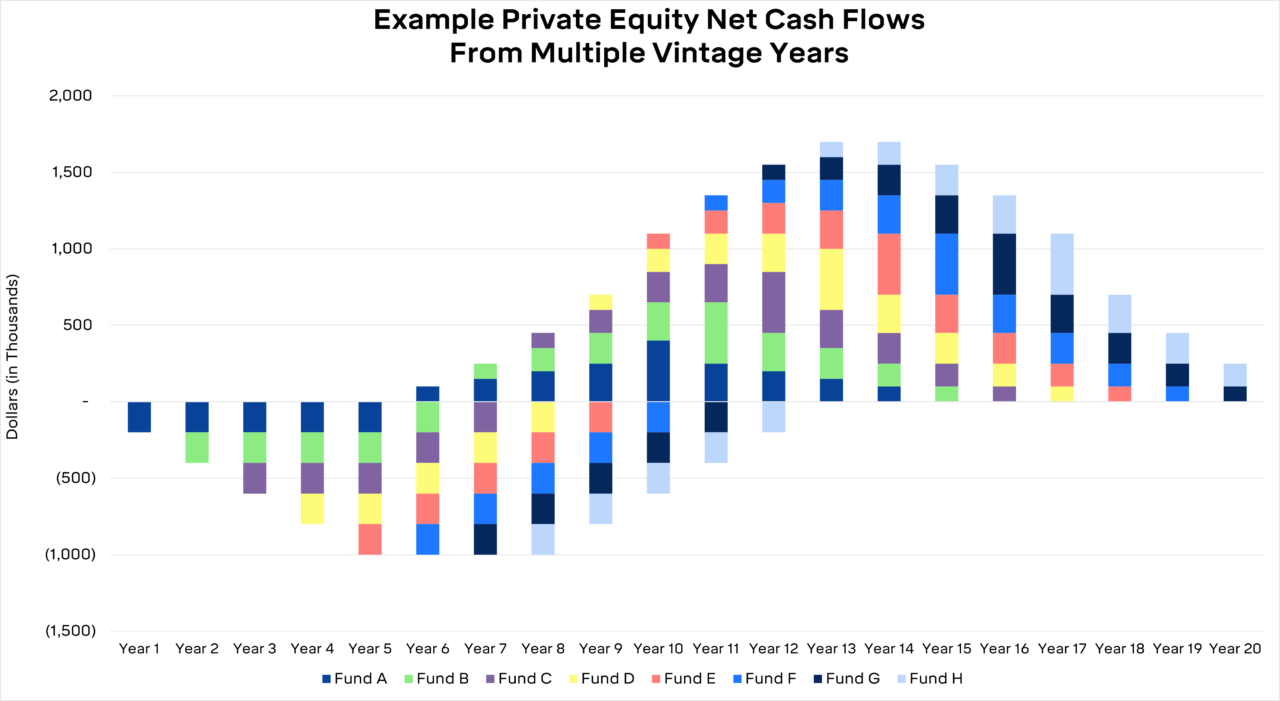

The example of Jane assumes committing to just one fund. In reality, the cash management challenge is more complex because building a private asset portfolio typically involves investing in multiple funds over multiple vintage years. The below chart shows what investing in funds over multiple vintage years looks like – it is somewhat more complex.

Cash Management Best Practices

The competing goals of having liquidity to meet capital calls and the desire to maximize investment returns are inherently at odds and unfortunately, there’s no silver bullet solution. Plus, each investor’s situation is unique.

While there are no hard and fast cash management rules, below are four best practices investors should follow.

1. Model Expected Cash Flows

As the Boy Scouts say, “be prepared!” which in the context of cash management means modeling capital calls and distributions. The GPs of private investment funds will provide some idea of the pacing of their capital calls. Investors should model the timing and amount of capital calls to understand liquidity needs. While distributions are less susceptible to estimation by GPs, modeling distributions is still a worthy exercise because distributions from a fund in harvesting mode can be used to meet the commitments of a newer fund calling capital.

The details of how to model private investment calls and distributions are beyond the scope of this article. However, Burgiss, a private investment data and analytics company, provides helpful guidance and insight on cash flow modeling in its paper, Modeling Cash Flows for Private Capital Funds. Further, some private investment data firms, such as Pitchbook, have tools that assist investors in commitment pacing and cash flow modeling.

2. Create an Investment Program

Building a high-quality private investment program involves diversifying investments by type (e.g., venture capital, growth equity PE, buyout PE, private real assets, private credit), geography, and vintage year and making commitments in a planned fashion.

Counterintuitively, investing in more funds across more vintage years smooths cash flows as variations in capital calls and distributions among individual funds offset each other and reduces the volatility of cash flows. For example, suppose that in 2023 Carl commits $5 million to a single private fund while Ron commits $1 million to five funds. Even though they’ve committed the same amount to private investment funds in 2023, Ron’s capital calls almost certainly will be less choppy because each of the five funds will find companies to buy in differing amounts and at varying times and thus call money at different times. Additionally, investing over multiple vintage years further smooths cash flow volatility. Thus, merely implementing a diversified investment program will solve some of the cash management issues.

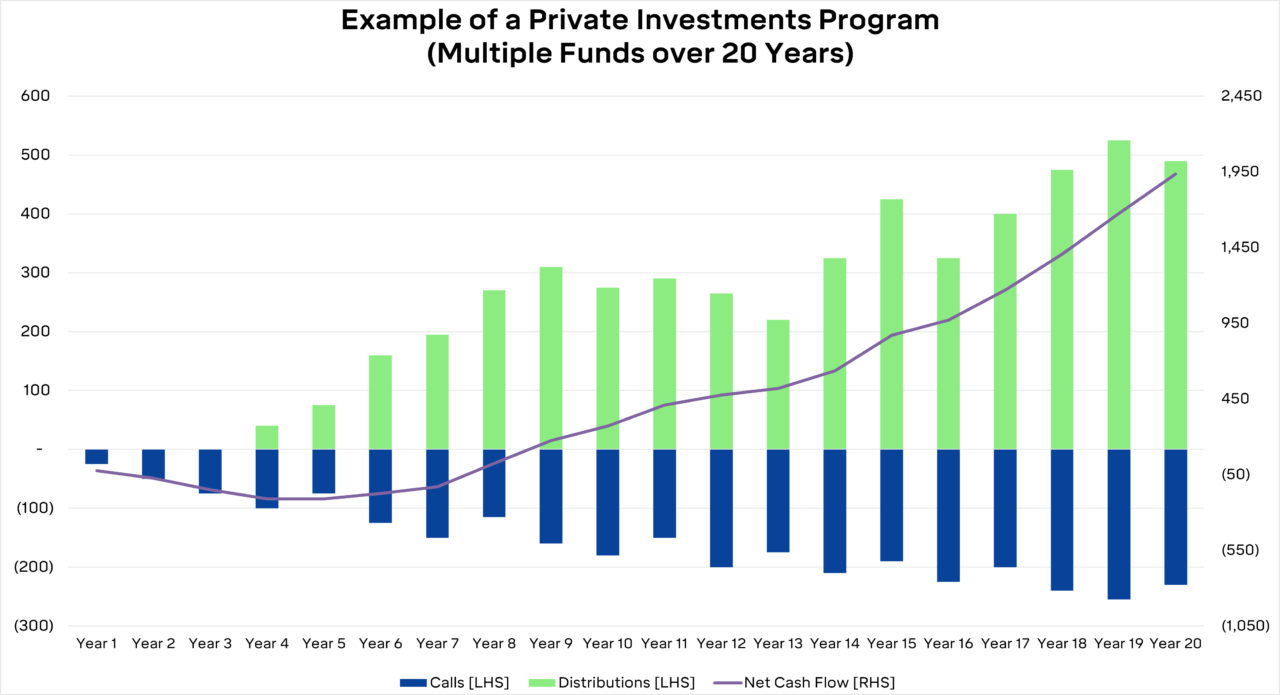

Eventually, a private investment program becomes largely self-funding as distributions from older funds are sufficient to cover the capital calls from newer funds. The below chart shows the capital calls and distributions for a hypothetical multi-fund multi-vintage year program over its first 20 years.

Note that a successful private investment program should result in more distributions than calls. In the above chart this begins in year six and cumulative cash flows are a net positive in year nine. Investors should have a plan for how to deploy net cash received from their private investment program (i.e., what amount should be held to fund future capital calls versus invested in the liquid portfolio?).

3. Err on the Side of Investing Rather than Sitting on Cash

Most investors won’t want to keep years of potential calls in cash due to performance drag. Having a quarter or two of expected capital calls is likely sufficient. Instead, investors generally should invest most of the money earmarked for capital calls across the public stock and bond part of the portfolio. As capital call notices are received, the available cash, or the temporary utilization of a margin loan, can be used to meet immediate capital call needs. Then cash can be replenished by raising money across the liquid investment portfolio (i.e., from the stocks and bonds) or when distributions from older funds are received.

The optimal strategy will depend on the details of the cash flow modeling, the composition of the liquid part of the portfolio, cash flow needs outside the private investment program, and individual investor risk tolerance.

Of course, the big worry is not having enough cash to fund capital calls during down years of the public portfolio. Yet, even considering general market volatility, if you commit to multiple private investment funds across numerous vintage years, there is a high likelihood of success by funding calls from a diversified portfolio of liquid investments and from distributions from funds in harvesting mode. Support for this strategy is found in a study covering the period of 1993-2013 by the investment firm Pantheon that found “investors in sufficiently diversified private equity portfolios could have invested up to 75% of unfunded commitments in public markets with low risk of defaulting on their commitments.” In the study, 75% in public markets means publicly traded stocks, so investing amounts earmarked for commitments in a 75/25 diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds should fit the bill.

Notably, other than the Pantheon study, which focuses on data ending ten years ago, there is scant research on the success of holding cash versus investing across the liquid investment portfolio. As the private investment data firm Pitchbook notes, “striking a balance” between holding cash or investing unfunded commitments, “is as much art as is it is science.” Again, modeling is key.

4. Have a Line of Credit or Margin Loan Capability

Because some capital calls occur with little notice (sometimes less than a week), having a line of credit or sufficient margin capability on the liquid portfolio is a must. Investors should not use debt as a long-term funding solution because of the risk debt adds to an investment portfolio. Instead, debt should be used temporarily as a funding mechanism and then paid down expeditiously.

Conclusion

Private equity, venture capital, and private real estate can enhance portfolio returns, but holding on to too much cash will counter some of the appreciation of those investments. For most investors, the best strategy is investing unfunded commitments across the liquid portfolio and merely keeping a quarter or two of expected calls in cash will minimize performance drag.