Two Axioms of Investing

There are two axioms (or accepted truths) in investing that are somewhat incongruous:

- The financial markets move in cycles; and yet

- The financial markets cannot be profitably timed on a consistent basis

Thus, while it seems CRAZY to ignore the ebb and flows of the market and invest in complete ignorance of the market cycle, it is also SENSELESS to invest in a fashion that relies on timing the cycle because timing is not effective. As investors, what do we do? How do we square this circle?

Markets Move In Cycles

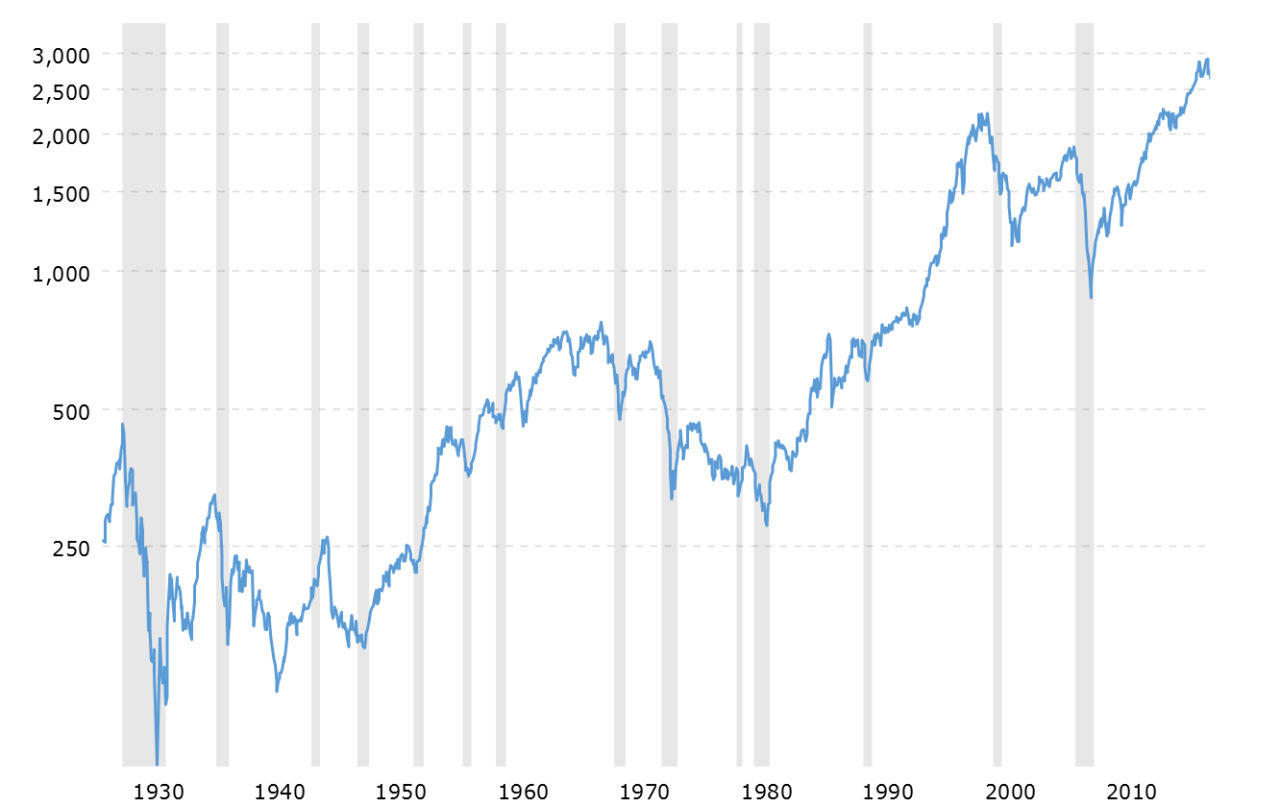

The financial markets are cyclical – the economy, the stock market and the bond market all move in cycles. As can be seen in the below chart of the stock market and economic recessions, the stock market almost always declines during recessions, but it can also decline even when there is no recession.

S&P 500 Index – 90 Year Historical Chart

(1927 – December 8, 2018)Grey shaded areas represent recessions

The adage that the stock market has predicted 20 of the last 10 recessions is apropos, and the fact that the economy and the stock market don’t necessarily move in lockstep is important for investors to keep in mind.

The financial markets fluctuate around a longer-term secular trend, and fortunately that trend has been “up.” However, the market volatility during an “up” trend can be rather extreme. Since 1970, the S&P 500 Index has averaged about a 10% annualized return, but in those 48 years it only had three calendar years with a return anywhere close to that average figure (between 8% and 12%). In comparison, the market has spent about one quarter of its time more than 20% away from the average (i.e. over 30% up or more than 10% down)!1

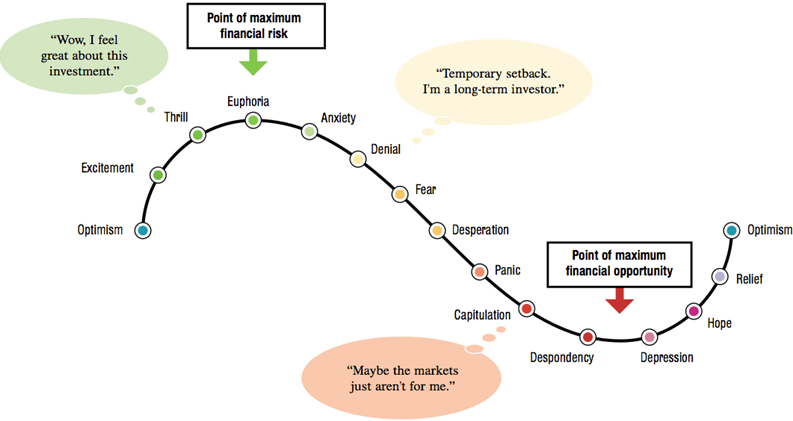

An important way to think of market cycles comes from the late economist Hyman Minsky who developed his “Financial Instability Hypothesis” in the 1970s. Minsky wrote, “A fundamental characteristic of our economy is that the financial system swings between robustness and fragility and these swings are an integral part of the process that generates business cycles.” Healthy investments during times of economic stability lead to speculative euphoria (often coupled with increasing financial leverage), followed by insiders taking profits; then panic ensues, and ultimately prices collapse which creates a recession or financial crisis.

Cycle of Market Emotions

Similarly, Howard Marks, legendary investor and Chairman of the investment firm Oaktree Capital, has distilled the bull and bear market cycles as follows2:

| Market Cycle Stage | Bull Market | Bear Market |

|---|---|---|

| First Stage | When only a few unusually perceptive people believe things will get better | Just a few thoughtful investors recognize that, despite the prevailing bullishness, things won’t always be rosy |

| Second Stage | When most investors realize that improvement is actually taking place | When most investors recognize that things are deteriorating |

| Third Stage | When everyone concludes things will get better forever | When everyone’s convinced that things can only get worse |

The key question is: where are we now?

Timing Market Cycles

Academic studies have concluded that it is not possible to profit from timing the market, at least not greater than mere chance would dictate.3 While this is a frustrating conclusion, it makes perfect sense. The price of financial assets is set by thousands or millions of buyers and sellers. At the market price, for every seller there is a buyer and every buyer there is a seller. If there were a proven factor or set of factors that signaled market tops and bottoms, then everyone would quickly know it; buyers and sellers would use such information to set their prices, and such signals wouldn’t work anymore. Therefore, to successfully time the market you must have information that correctly predicts a bear or bull market that isn’t widely known, yet in today’s information age, there are very few secrets.

Another major problem with timing the stock market is that to be successful you have to be right twice. Just getting out near the top isn’t enough, you also need to get back in near the bottom. Getting timing right once, let alone twice, is very hard to do. Revisit the chart of the S&P500 Index on the prior page. Sometimes a pullback in the market signals a bear market and a recession, and other times the pullback is just a breather before the market moves to new highs. Note that former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan warned of the “irrational exuberance” in the markets in December 1996 when the S&P500 was less than half of where it stood at its peak in March 2000. Similarly, Nobel Prize winning economist Robert Shiller advised long-term investors to get out of the market for the next decade due to historically high valuations in 1996; the market returned 6% annually over the subsequent ten years. The lesson: market cycles are nearly impossible to time.

Putting the Two Axioms Together – Five Best Practices

The two axioms taken together mean that with every additional day we are one day closer to the next bear market, but also one day closer to great investing opportunities that occur in the depth of bear markets. We just don’t know when these inflection points will occur. As we move through the market cycle, knowing that a bear market is looming is like seeing the headlights of a train in the distance but not knowing how far away it is while you stand on the tracks. The recent downturn in the market could be the start of a bear market or could just be a (healthy) correction before the markets head higher. Nobody knows. So, what should you do?

1 | Maintain Enough Liquidity to Ride Out a Bear Market

As we pointed out in our article “Five Lessons Learned Since Lehman’s Collapse,” when financial markets are under great stress, there is no substitute for liquidity. In the depths of the Great Recession, assets considered liquid – like municipal bonds and auction-rate preferred securities – could be sold only at discounted prices. Large endowments and foundations experienced liquidity crunches because of their sizeable allocations to illiquid alternative investments such as private equity, private real estate and hedge funds. Some endowments had to sell their interests in alternatives at deep discounts in the secondary markets. Likewise, many individual investors were forced to sell investment assets at depressed prices because they did not have adequate liquidity heading into the crisis. In 2008 and 2009 there was no substitute for having cash.

Our advice to clients is to have cash on hand equal to expected portfolio withdrawals for at least one year, and as much as three years. Having that much liquidity will allow them to ride out much or all of market stress. In addition, it is wise to have part of a portfolio in preservation assets such as high-quality fixed income that will act as “dry powder” during a down equity market.

2 | It’s Okay to Invest (or Stay Invested) in Advance of a Bear Market

History has shown that investing in advance of a bear market (or remaining invested) is not as bad as you might think, and sometimes it turns out great. As we pointed out in our article “Should I Sell Out of the Stock Market,” unless you call it perfectly, you are better off investing in advance of a bear market (assuming you are investing in a diversified and disciplined manner) than trying to time the markets. This statement may seem counterintuitive, but consider the following two charts that tell the same story over two different time periods. Each chart assumes an investor starts with $20 million of cash and invests in a diversified portfolio (about 70%/30% stocks/bonds) which is rebalanced quarterly. The $20 million of cash is invested in a lump sum on January 1st of each of the years indicated in the charts below.[/vc_column_text][image_with_animation image_url=”2416″ alignment=”center” animation=”None” box_shadow=”none” max_width=”100%”][vc_column_text]

The chart above shows that investing on January 1, 1998 (the green line) – about 2 ¼ years prior to the top of the market during the 2001 dot-com bubble – resulted in the best long-term returns. The second-best result came from investing on January 1, 1999 (dark blue line), only 1 ¼ years before the market top! Under all scenarios, the $20 million more than doubled.

The next chart goes through the same exercise over a shorter time period.

3 | Rebalance to Your Asset Allocation

The S&P500 Index has grown about 300% cumulatively since the market lows in March 2009. As such, it is possible that your equity portfolio has grown beyond its strategic allocation in absence of prior rebalancing or profit-taking. The great thing about rebalancing is that it is an unemotional way to sell assets when they are relatively high and buy other assets when they are relatively low. Following rebalancing discipline in up and down markets allows your portfolio to take advantage of the volatility of asset prices as they fluctuate around the long-term trend.

4 | Potential Mitigating Investments

In a perfect world, we’d be able to call market tops, move out of equities into cash and bonds, and then move back into equities at the market low. As discussed previously, this probably is not possible. In our experience, and as discussed under point 2 above, the best course is not to try to time the markets but instead be disciplined and rebalance through the market ups and downs.

If, however, you are concerned about the markets being near a cyclical top, there are certain types of investments that tend to preserve better on the downside but don’t give up all upside potential. Examples include use of active investment managers or passive funds that focus on low volatility or quality stocks. These styles of investing historically have preserved on the downside (i.e. captured less of the negative performance than the overall market). Another possibility is to invest in high dividend funds – the high dividends may help mitigate the downside.

5 | Be Wary of Portfolio Insurance or Investing in Market Neutral Funds

A possibility that we’ve explored with clients over the years is to buy portfolio insurance using derivatives like puts. What we have found is that buying portfolio insurance is very expensive and only likely makes sense if you are successful in calling the market top.

Another type of portfolio insurance is to buy a structured product like a principal protected note. While these may work in certain situations, there are a number of drawbacks that often lead us to recommend against this strategy as well, such as high fees, illiquidity and end point determinacy.

Finally, some types of hedge funds, such as market neutral or absolute return funds, may be a possibility for some investors to help mitigate the effects of a bear market. However, as with principal protected notes, there are significant drawbacks, the chief being that the returns of these types of hedge funds typically can be replicated with a simple mix of stock and bond ETFs for a significantly lower tax and fee impact. Additionally, their returns during the 2008-2009 time period were disappointing.

Conclusion

Solutions to the inconsistent nature of the axioms presented at the beginning of this paper are inherently unsatisfying. The markets will go down and taking steps to avoid the downturn while profiting from market upturns are generally not possible. The best practices are to have adequate cash and other non-correlated assets, remain disciplined and rebalance. In addition, some mitigating tweaks can be made to the portfolio in terms of tilting to low-volatility or quality factor exposure.

If you have adequate cash and follow your investment discipline, the ultimate best practice is to not spend time or emotional energy reading about or paying attention to the markets. STOP CHECKING YOUR PORTFOLIO! A long-term investor should not overly worry about the ups and downs of the markets. Most likely any investment moves, other than disciplined rebalancing, made near market tops or bottoms will hurt your returns. Instead of worrying about the markets, I suggest going on a walk, reading a good book and spending quality time with friends and family.

1 Example adapted from the book Mastering the Market Cycle, Getting Odds on Your Side, by Howard Marks (2018)

2 Stages of bull and bear markets from Mastering the Market Cycle.

3 See, e.g., John Graham and Campbell Harvey, “Market Timing Ability and Volatility Implied in Investment Newsletters’ Asset Allocation Recommendations.” Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 42, no. 3 (1996); and Damodaran, Aswath. Investment Fables: Exposing the Myths of the “Can’t Miss” Investment Strategies. New York: Prentice Hall, 2004. pp. 499-500.