Unlike classical economics, behavioral economics recognizes that human decision-making is influenced by biases and heuristics rather than being purely rational. Some of the biases highlighted by behavioralists include loss aversion, confirmation bias, hindsight bias, and overconfidence. However, another bias that is often overlooked in discussions of behavioral economics has a significant impact on decision-making in both investment and real-world contexts: the storytelling bias. I write about this bias in my book, The Uncertainty Solution: How to Invest with Confidence in the Face of the Unknown.

The Storytelling Bias

In their groundbreaking paper, “Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases,” Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, pioneers in the field of behavioral biases, described an American named Steve:

Steve is very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful but with little interest in people or in the world of reality. A meek and tidy soul, he has a need for order and structure, and a passion for detail.

Tversky and Kahneman then ask whether Steve was more likely to be a librarian or a farmer. I guessed librarian. I also imagined that Steve still lived with his parents, liked to wear sweater vests, and owned a cat. I doubted he had a girlfriend and figured he drove a nondescript compact sedan (nothing like my undervalued BMW). Maybe, like me, you made up a story about Steve based on Tversky and Kahneman’s brief sketch.

But the odds greatly favor Steve being a farmer. Why? It’s just math. In the United States, there are about 2.2 million male farmers and just 25,000 male librarians. That means there are eighty-eight times as many male farmers as male librarians. So, it’s possible but highly unlikely that Steve’s a librarian.

Don’t feel bad if you jumped to the same conclusion as I did. We rarely stop to consider base rate probabilities. Instead, it’s human nature to view the world through stories and ignore, as Kahneman and Tversky put it, “the statistics of the class to which the case belongs.”

Stories Are More Powerful Than Facts

From a physical standpoint, you wouldn’t bet on Homo sapiens becoming the Earth’s dominant species. We don’t have sharp teeth and big jaws, we lack fur to keep us warm, and we’re slower and weaker than lions and tigers and bears. (Oh my!) Ants can carry twenty times their body weight. Our senses—sight, hearing, smell, etc.—are vastly inferior to felines, canines, the great apes, birds, and others. We Homo sapiens rule the globe (more or less) because of our ability to work together in large groups toward shared goals.

In his book Sapiens, historian Yuval Noah Harari suggests three major revolutions in our species’ history: a cognitive revolution about seventy thousand years ago, an agricultural revolution ten thousand years ago, and a scientific revolution five hundred years ago. These three developments allowed humans to leap to the top of the food chain very quickly (on an evolutionary timescale). Of the three, the cognitive revolution was the biggest driver of our species’ survival and success. That happened when we developed language and, with it, the ability to communicate abstract ideas.

Storytelling allowed us to create and share complicated ideas efficiently, and stories enable large groups of strangers to identify and work together. According to Harari:

Any large-scale human cooperation—whether a modern state, a medieval church, an ancient city or an archaic tribe—is rooted in common myths that exist only in people’s collective imagination. States are rooted in common national myths. Two Serbs who have never met might risk their lives to save one another because both believe in the existence of the Serbian nation, the Serbian homeland, and the Serbian flag. Judicial systems are rooted in common legal myths. Two lawyers who have never met can nevertheless combine efforts to defend a complete stranger because they both believe in the existence of laws, justice, human rights—and the money paid out in fees.

Everything that Harari mentions (nations, laws, money) is conceptual; none of it has a physical reality; they’re agreed-upon fictions. Stories have the almost magical ability to make events and things that don’t tangibly exist inculcate values, like the story of underdogs fighting for freedom as in the Star Wars movies or stories of a hero’s journey like in The Odyssey. The difference between the real and the imaginary, finally, is not that important.

Without stories, we couldn’t pool our resources as we do, becoming greater than the sum of our parts, or maintain our complex social structures. Stories lead people to believe in shared goals and purposes.

Much of our interactions with other people consists of telling stories. I tell you a story about something that happened to me; you respond with your own story, and this lets me know that you understand the story I told you. And so it goes, back and forth.

We identify other people as members of our group or tribe if they tell similar stories. For example, in September 2021, I attended my first face-to-face conference since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The conference started off with lunch. I was randomly seated with seven other people. After brief introductions, we started sharing stories about when, if, and how our offices opened back up; the challenges of working from home; and what share of our respective workforces were vaccinated. We quickly realized that we all had similar experiences and challenges. We bonded and made it a point to stop and chat with each other throughout the conference. Exchanging stories around a lunch table created a mini tribe for the duration of the conference.

Because we’ve evolved to be storytellers and story exchangers, we pay special attention to stories; they greatly influence our worldview and our decisions. A single story can exert more sway over our decisions than reams of data, analysis, and statistics.

Base Rate Ignorance

A study published in 2004 illustrates how much power stories have over us. Volunteers acted as patients. The researchers told them they had a fictitious disease called Schistomanliasis, an infection caused by a parasitic worm that, if left untreated, would result in death within a year or two. Two drugs (also imaginary) were presented as treatment options: Fluortrexate and Tamoxol.

Fluortrexate, the patients were told, cured Schistomanliasis 50 percent of the time; Tamoxol’s effectiveness was presented as variably as 30 percent, 50 percent, 70 percent, or 90 percent effective. So, the patients had to choose between Fluortrexate, at 50 percent effective, or Tamoxol, at one of the various effectiveness rates.

If the study had stopped there, it would be unremarkable because the participants would have surely picked the treatment with the highest rate of efficacy, whichever that happened to be. The twist was that the researchers told the participants about the outcomes for two patients before asking them to pick their drug. For Fluortrexate (the control drug) at 50 percent efficacy, the story was neutral:

Chris was unsure if the decision was right or wrong (i.e., was ambiguous). Doctors were not certain whether the worm was destroyed. Doctors were unable to determine whether the disease would resume its course. At one-month post-treatment, Chris is having good days and bad.

For Tamoxol, the participants were told one of two different stories: (1) a positive outcome history, or (2) a negative outcome. The positive story:

Pat’s decision to undergo Tamoxol resulted in a positive outcome. The entire worm was destroyed. Doctors were confident the disease would not resume its course. At one-month post-treatment, Pat’s recovery was certain.

The negative story:

Pat’s decision to undergo Tamoxol resulted in a poor outcome. The worm was not completely destroyed. The disease resumed its course. At one-month post-treatment Pat was blind and had lost the ability to walk.

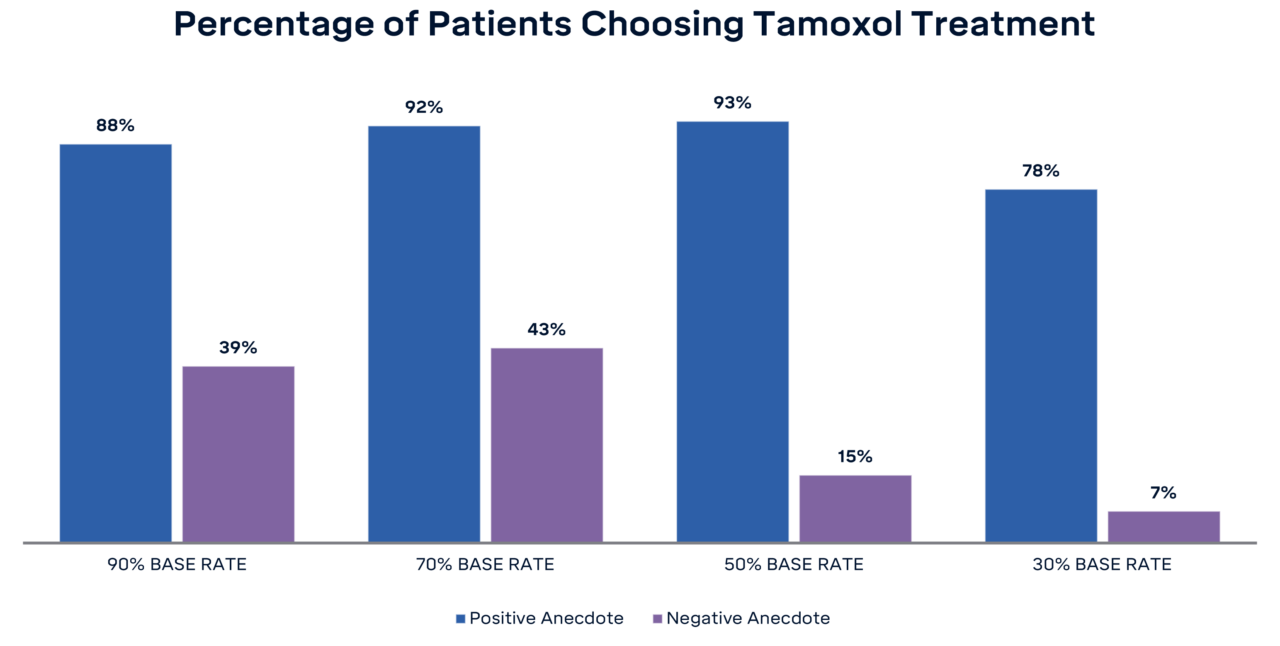

The story of a single patient’s outcome, told different ways to different groups, turned out to have a massive impact on the drug chosen. The treatment decisions are summarized below.

ST. LOUIS TRUST & FAMILY OFFICE

If stories didn’t sway the decision making, the participants would have chosen Tamoxol 100 percent of the time when it had 90 percent or 70 percent effectiveness because Fluortrexate had a lower base rate of success of 50 percent. And no one would have (or should have) chosen Tamoxol when it was just 30 percent effective. But that’s not what happened. As shown in the above chart, when Tamoxol was presented as being 90 percent effective paired with a negative story, only 39 percent chose it.

This is an astounding outcome. Stories about a single patient’s experience made the study participants throw the base rate out the window and make a bad decision.

Story Lessons

The world of investing is full of stories. Investment managers tell stories about their past successes and about what opportunities the future holds. Our friends and acquaintances tell us stories about their successful investments at cocktail parties and social gatherings. The financial media tells stories about threats and opportunities in the economy and the market. We’re bombarded with stories. And we’re swayed by them because that’s how we’re wired.

Developing a mental model about stories is essential to successful investing. That starts with understanding that a story will have an outsized effect on your decision making. Train yourself to seek out the base rate (as with farmers and librarians or drug treatment options) and add that to the mix. For example, when considering an individual stock, set aside the stories related to the stock and realize that most stocks underperform the market, so the odds are against your single stock pick being a good idea. Or, when considering a start-up company with a compelling story, think about the base rate statistics for start-ups: less than 50 percent make it to their fifth year, and 70 percent fail within ten. And when considering an actively managed fund, remind yourself that the vast majority of active managers underperform the market after fees. This will help counterbalance the stories they tell about their successes.

Learn to recognize when you’re being told a story and realize that the story will have an outsized effect on your decision making.